Paranoid polyglots beware. After years of brushing off comments like “don’t you ever get mixed up with all those languages?“, it happened to me recently: I noticed a significant interference from one language to another.

The pernicious pair of languages comprised German, my longest and strongest project, and the not-too-distantly related Norwegian, which I started much later, but also speak reasonably well. The culprit? The word for vegetarian. After years of being perfectly aware that the German translation is “der Vegetarier“, I found myself starting to say “der Vegetarianer” instead. Norwegian shuffles and looks sheepishly at its feet in the corner; the norsk equivalent is “vegetarianer“. Guilty!

Since adding Norwegian to my languages, it seemed I had also added an extra syllable to a German word, too.

This kind of interference is especially common with close sibling and cousin languages. For example, difference can arise when close languages borrow words differently, ending up with mismatched genders for cognates as in this example. Similarly, when I first attempted to speak Polish, the interference from my similarly Slavic Russian was inescapable.

Evidently, polyglots are regularly learning material that lends itself to cross-confusion and interference. But we often worry about it, or characterise it as some kind of failure of method, when there is good reason not to.

Bilingual brains

Firstly, interference is a wholly normal feature of using more than one language regularly. Research into bilinguals reveals that even two native languages are not immune from interference.

But more importantly, cognitive linguists studying bilingual subjects have illuminated some of the brain processes that monitor and catch such slip-ups, and, crucially, learn from them. Now, polyglot language learners are not quite analogue with bilinguals. But these conclusions go some way to explaining processes that affect us all, and more practically, reassure the paranoid polyglot.

Our inner sentinel

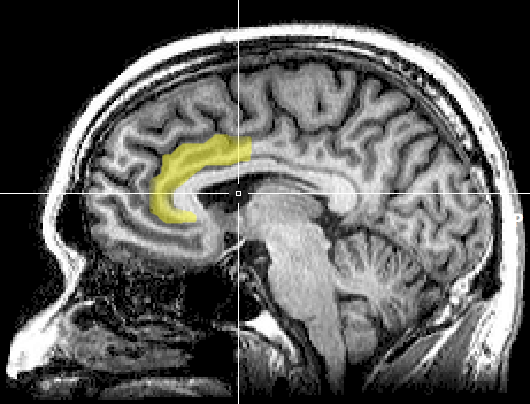

The key topic of interest in cognitive psychology here is conflict monitoring theory. This approach to understanding thought probes what happens in the brain when errors creep into our conscious stream. One particular structure, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), appears to be our inner sentinel, monitoring activity and sounding the alarm when “competing representations” come into focus.

The location of the anterior cingulate cortex in the brain. Image via Wikipedia.

Note that it is our own brains doing the detection. We know, on some level, that we have made a mistake. That in itself should be sweet reassurance to the worried learner. Our brains are simply not constructed to rattle off mistakes without recourse to self-correction. If you are familiar with the material, interference will always ring bells.

However, the anterior cingulate cortex appears to do its work beneath the level of conscious control. We are not even aware of it, save for the mental jolt we get when we realise something was amiss. That neatly explains that familiar niggling feeling when something questionable leaves our mouths!

Intuiting interference – some strategies

In fact, the research goes beyond plain reassurance. One study of bilinguals concluded that regular language switching will increase error detection. That will be music to the ears of polyglots pondering the sense of studying more than one language at once. It suggests a strategy for success: cycling through your languages regularly, rather than focusing on one at a time. This chop-and-change approach may help keep your ACC sentinel fired up to ambush errors.

Some platforms such as Duolingo are perfect for switching to and fro between active languages like this. It was using this very resource that I noticed my own Vegetarier-vegetarianer interference slip above. The site’s multichoice flavour of questioning in particular is a great way to flex the brain in terms of conflict monitoring and error correction. Faced with one correct response and two – often subtly – incorrect ones (often cheekily bearing a resemblance to another red herring language), those mental circuits receive a proper taxing.

Finally, let’s not forget regular speaking practice using online services like iTalki, too. Once, I would fret at the potential confusion from practising three or four different languages in a week. As it turns out, that could be just what we all need.

And those pesky Russian interferences in my Polish? Well, after a bunch of lessons, and a fair bit of forehead-slapping and self-chastising, they have thankfully vanished. Like my interference errors, yours will struggle to escape the watchful eye of your anterior cingulate cortex in the end, too.

The take-home message? Don’t fret too much about interference, and revel in your multiple languages. Your anterior cingulate cortex has your back!